Artist Note #22 – Who Ate Up All the Shinga?

January 22, 2023

I don’t know what makes this an artist note post versus a note about books. It seems that I separate the idea between the two, and then at other times, merge them. There is no particular rhyme or reason. It feels like an artist’s note to talk about Park Wan Suh, a Korean female writer who wrote prolifically in her 40s to her death due to complications from gall bladder cancer.

I would not have known about this author or the book, Who Ate Up All the Shinga? (contains affiliate link), had it not been for a class this winter.

Park Wan Suh’s story resonated with me because she debuted in the Korean writing scene when she turned 40. She kept going and wrote so much coming back to the familiar themes of her family, mother, traumas of the Korean War, Japanese colonization of Korea, and commentary on the middle-class social structure.

Notes from Week 1 Reading

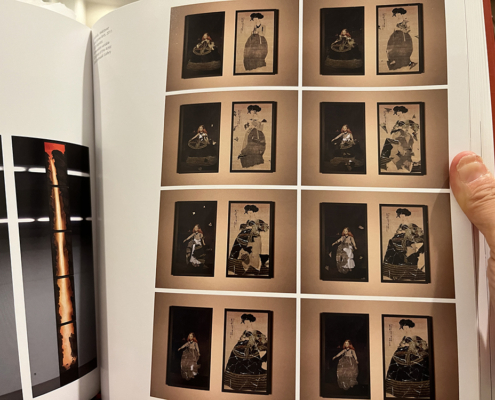

I found the self-portraits of Na Hye-sok and Ko Hui-dong to be in stark contrast to one another. At first glance, Ko’s three self-portraits look different in composition, line, texture, and form. But upon closer inspection of his work and further reading of Kee’s historical context of Ko’s political and cultural climate, I notice that he clung to the use of indirect lighting (aka soft lighting) of the subject (himself). Comparing his Self-Portrait in Overcoat to his latter two pieces, one can see how Ko moved from simple textures and lines to add more detail, such as creases in the clothing and his face. His move from a traditional portrait to environmental portraiture also provided more insight into his life and lifestyle. Ko, who studied in Japan, struggled between his Korean culture and the influences of Western culture and Japanese imperialism, which can be seen in his paintings. In Self-Portrait with a Hat, using oil painting as his medium, he tries to emulate the painting in Asian ink brushstroke painting. His return to ink painting in 1925 shows how he felt the need to hold onto his Korean culture and traditions.

Na’s self-portrait, on the other hand, uses direct lighting creating strong, harsh shadows on her face. Created in 1928, Na’s self-portrait somewhat resembles the form of Ko’s Self-Portrait with Fan. Both portraits pull away from the subject and show the subject from a ¾ view (from head to hip-thigh level). But Na’s portrait looks directly at the viewer in deadpan. (All three self-portraits of Ko have the subject looking beyond the viewer’s gaze. In fact, I would say that with each iteration, Ko’s self-portraits have each subject’s gaze look further and further beyond the vantage point of the viewer.) When reading “Kyong-hui” (K.H.), Na is questioning how women are viewed from the perspective of four different conversations: 1) between the mother and K.H.’s mother-in-law (older woman to woman), 2) rice cake peddler (outsider and self (K.H.), 3) father and mother/husband and wife, 4) K.H. herself. Through the use of storytelling, Na is asking the reader to look directly at the cultural norms and expectations placed on Korean women. Just as in her writing, Na is also asking the viewer to look directly at her self-portrait.

Notes from Week 2 Reading

As I read Who Ate Up All the Shinga? I couldn’t help but think about the accuracy of Park’s childhood memories. She was as early as seven years old when she recounts her memories of growing up in the countryside and the traumatic move to Seoul. Not that I discount her memories or words in the book, but as I discuss and recount my children’s perspective of certain family moments, I noticed that they have a skewed perspective of their memories. For example, one of my kids would say, “Ummah, remember the time when we did X?” They would then go into painstaking detail about the memory of an image that I had taken on my smartphone. So, whose memory are we talking about at that moment? Mine at the moment the image was taken as the photographer or my children who happened to be the subjects in the image (then later as viewers of the image)?

I also couldn’t help but compare Park’s book to Ten Thousand Sorrows by Elizabeth Kim (Amazon affiliate link). Kim’s book was hailed as a beautiful memoir about a Korean adoptee who moved to America after a white couple adopts her from a small Christian orphanage. Kim’s book received some criticism for some inaccuracies in her timeline. But I think Park did a thorough job of researching present-day locations of past places, such as a school that she or her brother once attended, which is now located somewhere in Seoul. Park is more direct about informing the reader of her memories as if breaking the fourth wall to speak to us. I think I appreciated the attention to detail in Park’s research and perspective compared to Kim’s Ten Thousand Sorrows.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!